Through June 24th, Opera Theatre of St. Louis presents the world premiere of “Awakenings,” based on the book of the same name by Oliver Sacks. With music by Tobias Picker and a libretto by Picker’s husband, neuroradiologist Dr. Aryeh Lev Stollman, “Awakenings” takes on the difficult task of turning a plot-free nonfiction work into a dramatically coherent piece of musical theatre—and a few missteps aside, it succeeds splendidly.

Sacks’s book is the story of the famed neurologist’s heroic but ultimately unsuccessful attempts in the late 1960s to treat patients at New York’s Beth Abraham Hospital who were suffering from encephalitis lethargica. A mysterious disease that infected at least a million people (and killed at least half of them) during a worldwide pandemic between 1915 and 1926, encephalitis lethargica left many of its survivors in a kind of netherworld—awake and apparently aware, but largely nonresponsive to everything and everyone. “They neither conveyed nor felt the feeling of life,” wrote Sacks; “they were as insubstantial as ghosts, and as passive as zombies.”

|

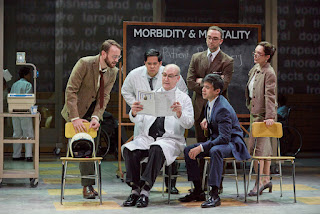

| L-R: Katherine Goeldner, Andres Acosta, Marc Molomot, Jarrett Porter Photo: Eric Woolsey |

Sacks tried to treat them with L-DOPA—a drug used primarily to reduce the symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease, many of which are shared with encephalitis lethargica. At first it appeared to be a miracle cure and was described that way in the press. Unfortunately, the reprieve didn’t last, and the patients eventually slipped back into their former half-lives after experiencing a painfully brief return to full ones. The pandemic stopped as mysteriously as it started, and to this day there is no real cure.

The opera tells this complex story by focusing primarily on three patients: Miriam H., Rose, and Leonard Lev. Miriam and Rose are composites of real people from the book, as are most of the other characters, but Lev is, as Joshua Barone writes in The New York Times, “largely intact and is even intensified.” Sacks himself is also present, both as narrator and as a character struggling with his own awakening to his identity as a gay man—something disclosed publicly only a few months before his death in 2015.

That multi-layered approach has both its strengths and weaknesses. Leonard, Rose, and Miriam are all fully realized and immensely sympathetic characters whose stories are both beautiful and heartbreaking. Their scenes are, far and away, the most compelling aspects of the opera. So much so that Sacks’s own story, while tragic in its own way, feels almost trivial by comparison.

|

| L-R:Adrienne Danrich, Susanna Phillips Photo: Eric Woolsey |

A subplot involving the unrequited love of the nurse Mr. Rodriguez for Sacks and Leonard’s equally futile love for Rodriguez feels imposed and unnecessary. And a flashback in which the young Sacks is suddenly and harshly rejected by his mother because of his sexual orientation comes across as implausible and clumsy. It does, however, set up one of the stronger moments in the opera, a long monologue in which Sacks realizes there are some things that “can’t be changed by me. Not with medicine or love.” He laments that “there is a border I can never cross”—echoing the same words sung by Rose as she describes the experience of falling ill decades before.

So, yes, “Awakenings” is a mixed bag, dramatically speaking. But the mix is heavily positive. And, given that this is a world premiere by a librettist who has never attempted an opera before, it’s really quite admirable. Better yet, Picker’s music has a strong emotional connection with Stollman’s words—something I have not always heard in some other contemporary operas. Surprisingly for someone who studied with composers like Elliott Carter and Milton Babbitt (who treated music more as a mathematical exercise than a form of communication), Picker has written a score that often embraces melody and is perfectly matched to the natural flow of the text.

Part of this is likely due to the fact that Picker and Stollman worked as a team in creating “Awakenings,” writing music and lyrics together. In that sense, the work hearkens back to the musical theatre pieces of legendary teams like Rodgers and Hammerstein, Lerner and Loewe, or Flaherty and Ahrens. I often come away from newer operas with the feeling that the composer and librettist inhabited different worlds. Not so with “Awakenings,” which feels like the true partnership that it is.

|

| David Pittsinger and the cast Photo: Eric Woolsey |

Every member of this large cast (15 named roles) does a splendid job, making even the smallest character well-rounded and credible. Tenor Marc Molomot’s deeply troubled Leonard is a beautiful piece of work, and the character’s tragic fall into madness is deeply moving. Mezzo Katharine Goeldner offers sympathetic counterpoint as his long-suffering mother Iris.

Sopranos Adrienne Danrich and Susanna Phillips are (to quote Mr. Sondheim) a “practically perfect pair” as Miriam and Rose. The fast friendship that develops between the two is both heartwarming and, ultimately, heartbreaking as their illness snatches them back into the Twilight Zone. Two other patients, Frank and Lucy, are brought to vivid life by tenor Jared V. Esguerra and mezzo Daniela Maguara. Tenor Andres Acosta powerfully communicates Mr. Rodriguez’s frustrated yearning.

Bass-baritone David Pittsinger, whose stentorian tones have graced both operatic and musical theatre stages, is Dr. Podsnap, the hospital’s Medical Director. The character’s Dickensian name is a good match for his snobbishness and refusal to even consider the research behind Sacks’s proposal. “Who does this Englishman think he is,” he snarls. “Another fancy paper / It will be disproven before you know it.” It’s not until the final scene that we get to see the emotional conflict that lurks behind that arrogant front. “Have I broken my oath,” he muses. “Can it be wrong to have tried? I don’t know. Though in the end I did not protect them.” Pittsinger’s multi-leveled performance captures both sides of Podsnap’s persona.

|

| LR: Andres Acosta, Jarrett Porter Photo: Eric Woolsey |

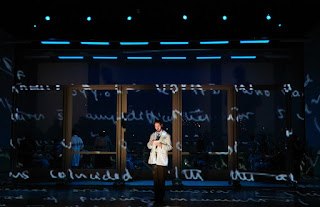

Much of the opera, of course, rests on the highly capable shoulders of baritone Jarrett Porter as Sacks. Picker and Sacks were close friends, and the fictionalized version of him in the opera has the ring of truth and compassion. A complex mix of crusader, healer, and a conflicted man who (in the composer’s words), “finds himself locked in by outside social and familial forces,” the character of Sacks requires not just a compelling singer but also an actor capable of showing us his many facets. Porter is just the man for the job. It’s a bravura performance.

The OTSL chorus has all of its usual power, although Picker’s thick choral lines are difficult to hear, requiring frequent glances at the English supertitles. Even so, I was especially impressed by the clarity with which the singers handled the short, sharp phrases lobbied back and forth in the contentious clinic scenes. Lines like “Hyoscamine! Stinking nightshade! Anticholinergics! Belladonna!” are not often heard on the opera stage and don’t fly trippingly off the tongue.

Under Roberto Kalb’s direction, the orchestra gives what certainly sounds like an authoritative reading of the score. Judging by the hugs and smiles when both Picker and Stollman came on stage afterwards, the creators of “Awakenings” would appear to agree.

OTSL Artistic Director James Robinson, who directed Picker’s “Emmeline” in 2015, repeats that role here, imparting a sense of momentum and even urgency to a work that could, in lesser hands, become static. Robinson has brought most of his production team from “Emmeline” along as well, with satisfying results.

Allen Moyer’s set is simple and flexible, consisting of a series of transparent panels that are easily rolled around the hospital ward set to create different playing areas. Christopher Akerlind’s lights and Greg Emetaz’s video projections allow the scene to shift easily from the hospital interior to the botanical garden outside, where the recovering patients, in a touching scene, make their first contact in decades with the natural world. James Schuette’s costumes subtly reflect the personality of each character. The brown British tweeds Sacks wears in his first appearance, for example, clearly mark him as on outlier among the American hospital staff.

|

| Jarrett Porter in the final scene Photo: Eric Woolsey |

Opera Theatre’s “Awakenings” is not, of course, the first attempt to dramatize the Sacks book. The 1990 film version is perhaps the best known of those attempts, but in 1980 Harold Pinter made it into a one-act play titled “A Kind of Alaska” and Picker himself composed a ballet version in 2010. There was even a 1974 documentary for British television. But this world premiere is the first try at a full-length work for the stage, and despite its flaws it’s well worth your time.

“Who knows if the world out there will ever truly know us,” wonders Miriam in the final scene. “Who in the world could ever truly know us?” “Awakenings” is another step towards that level of understanding.

“Awakenings” continues through June 24th at the Loretto Hilton Center on the Webster University campus in rotating repertory with the rest of the Opera Theatre season. To get the full festival experience, come early and have a picnic supper on the lawn or under the refreshment tent. You can bring your own food or purchase a gourmet supper in advance from the OTSL web site. Drinks are available on site as well, or you can bring your own. For more information, visit the web site.

No comments:

Post a Comment